The problems facing Corporate America - and its employees - today are the same as the problems facing Corporate America for decades.

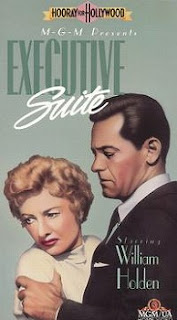

In the 1954 movie Executive Suite, William Holden and Barbara Stanwyck fight for control of her late father's company. The company, Tredway Industries, is a furniture manufacturer, and has fallen into the hands of bean-counting accountants who want to cut quality and boost profits - putting shareholder returns above all else, even the long-term health of the company. It is a plot that could have been drawn from today's papers and illustrates how the economic forces affecting American industry have remained little changed over the decades.

Louis Auchincloss, as I noted before, wrote a book describing a dynastic family that owned a famous glass company and glass museum (which of course, was not Corning!). One of the central arguments in the book was whether the company should introduce a line of more cheaply made glass products for general consumer use, in order to boost profits and be able to meet salary requirements for unionized workers. Many of the family members were appalled that the family name would be attached to something of lesser quality, even if it was profitable.

General Motors, of course, struggled with this problem, and John Delorean wrote of the wars with the "bean counters" who took over the 14th floor and wrested control of the company from the Engineers. To increase profits, they cut the costs of manufacturing, eliminated different car models and engine models, and made all the cars look largely the same. While in the 1960's, GM was offering air-cooled rear-engine Corvairs, turbocharged V-8s, fuel injection, aluminum block engines, overhead cam inline sixes, by the mid 1970's, engine choices were largely reduced to the 350 and 305 small block Chevies, and an inline and V-6 engine, as well as a tired old 4-banger.

Other companies, in the 1970s and 1980s, were bought out by larger conglomerates, who gutted the quality of a product, increased profits, and rode the wave, until consumers figured out that the product was no longer what it once was, and stopped buying. A company can "coast" on brand reputation, but only for so long.

AMF, for example, bought Harley-Davidson and nearly drove it into the ground, as quality dropped and prices surged. At one point, it looked like this historic bike maker was headed for oblivion. Today, much has changed, and AMF is no longer at the helm.

What causes this sort of problem? If you are a Wall-Street protester, you might argue that the "Greedy investment bankers" are to blame. But of course, as small-investor shareholders, we all want to see fat dividends and robust stock prices, right? Few people today are interested in the long-term health of a company, particularly when they are trading the stocks on a weekly basis.

And yes, management is to blame, as they get bonuses based on the stock price, and thus their incentive is to increase stock price for the short-term, at the expense of long-term profitability. Changing those incentives, of course, is the key to changing manager's motivations.

But another problem exists - if a company is "under-performing" - which is a code word meaning that it could be bought, stripped down, flogged for a quick profit, and then tossed away - someone might try to take over the company by promising the shareholders a lucrative buy-out or lucrative profits. And this happens to many companies, not only today, but decades in the past. Takeovers and proxy fights are nothing new.

Consumers also drive this model as well. We all whine and complain about how Wal-Mart exploits the masses and how all our jobs are being outsourced by those "evil corporate overlords". But we also like the cheap products from China. Where do you think they make those iPhones, anyway? Most of the gear that the "occupy" protestors have, including their tents, their clothes, their sneakers, their smart phones, and their generators (!!) are all made overseas, in part or in whole. And they wonder where their jobs went?

And of course, the workers are not entirely innocent in this matter, either. Over the years, powerful unions have demanded - and received - generous salary and benefit packages, even as they knew that their wages and benefits were two to three times the competing norms in their markets. They knew that these increased labor costs would make the company uncompetitive with its non-union neighbors, and certainly with its overseas competitors, but like the greedy management what gladly signed such contracts in exchange for labor peace, they figured they'd take what they could get, while they could get it, and to heck with the future or the next generation. And empty abandoned factories all over the Northeast are the result.

So it is not any one group that is to blame - nearly everyone who is associated with any company or concern is interested in getting as much out of it as they can. And if you think about it, not only is that basic human nature, but basic economics, as well.

There is no easy fix for this situation. And perhaps there need not be. After all, a factory or a business is not forever. In the movie Executive Suite, William Holden tries to take control of the furniture company from the bean counters, so that they can make quality, modern furniture that people want, and not inexpensive cheaply made crap that the accounting department wants, for profit reasons.

But suppose Holden failed? If his ideas had merit, would not some other manufacturer have filled in the void and the bean counters at Tredway been proven wrong? After all, there is more than one furniture factory in the world.

In 1954, a furniture manufacturer must have seemed to be a pretty solid industry. Today, perhaps less so. I wonder, if William Holden would have been successful in real-life in turning around "Tredway Corporation" I suspect the net result would have been that Tredway would no longer exist today. People today flock toward cheap furniture made overseas, from places like Ikea or Ballard Designs. Few people today buy Stickley. Most want cheap particle board, even if it falls apart after a year or so. Perhaps the plot of the movie was a bit of idealistic naivete or Socialist propaganda.

Factories, like cars, houses, space shuttles, and anything else man-made, wear out over time and need to be scrapped and replaced. Moreover, they become obsolete, like anything else man-made. While it might be a nice socialist fantasy that the "old furniture factory" in town be kept running, so that old Gus will still have a job, if the factory is inefficient and outdated, and the products are unaffordable, it needs to go.

And perhaps, in this regard, the bean-counter approach has some merits. After all, the point of a corporation is to make money and a return on investment. It may be nostalgic to keep the old factory running - but maybe not practical over time. Many of the empty factories in New England went out of business because their products became obsolete and the factories became outdated. Trying to save them would be an exercise in futility. Conversion into lofts is probably the only bet. Emotions should not trump economics.

And let's face it, where was Tredway Corporation, back in 1954, dumping its waste varnish and other debris? Yup, into the river, no doubt, and the volatiles were evaporating right into the air - those that were not going right into old Gus' shriveling lungs. While we might wax nostalgic about the old factory shutting down, we forget about how we felt about it when it was in business. Pittsburgh, during the steel mill era, was a nasty and dirty town, clogged with pollution and ugliness.

Executive Suite is a bit of Communist agitprop, in that regard. The premise is that if only emotional people with a vision and a dream could run things, everyone would be better off - and boo and hiss on those "bean counters" who want to run things efficiently. In other words, let the educated elite take charge and tell us what is best for us - the ivory tower idealists, who will become our Commissars, once the revolution takes place.

The Soviet Union followed this model - all the way to its grave. They kept factories running long after they, and their products, were obsolete.

So, while we decry outsourcing, and "bean counters" allegedly ruining our American way of life, to some extent it is we ourselves, in the form of consumers, workers, investors, and managers, who are flogging our own businesses for every last penny. And this is how economics works - and perhaps should work.

And the market will determine, in the long run, which approach is right. GM followed the route of de-contenting and bean-counting - and went bankrupt. Meanwhile, BMW and Mercedes kept offering more complicated, well-built, and expensive cars in the USA, and people bought more and more of them. While GM was in the throes of bankruptcy, BMW was the most profitable car company on the planet.

Whose approach was correct? In this instance, you might argue it was BMWs. But it is easy to pick winners in hindsight. And perhaps, if we let the market determine who is right and wrong, those who make the bad calls will go away, rewarding those who made the right ones.

Alas, it is never that easy. We bail out GM (much as the Soviets propped up their industries) and GM can now can re-content its cars. Meanwhile, VW and Honda, stuck with rising costs, decide to de-content theirs. I wonder where this will lead?