Housing prices fluctuate due to more than supply-and-demand and inflation. Monthly costs can make prices swing wildly.

Houses are like any other commodity, subject to the ordinary pressures of supply and demand and inflation. Some folks like to say they are "different" somehow, in that the supply of land is finite. This may be true, but the supply of oil, bauxite, and pork bellies is also finite, and yet these things have commodity prices and are not deemed "unique" in any way. Saying houses are "unique" is just another bullshit argument Real Estate Agents use to sell houses.

The quote, supposedly attributed to Mark Twain (among others ) of "Buy land! They aren't making any more of it!" has bankrupted more amateur investors than anything else. Yes, they might not be "making any more of it" but if you pay too much for any commodity, no matter whether it is finite or not you can lose your shirt.

If you pay too much for a house, to the point where you will never make your money back or spend decades hemorrhaging cash trying to pay a mortgage, you will never come out ahead. In addition to land, our lives are also finite, in particular our working lives.

So what affects the price of houses - or more precisely, how do housing prices get to where they are? Well the most obvious reason is supply and demand. Again, the idea that the cost of something is equal to the cost of raw materials "plus a modest profit" is naive thinking. Any commodity is worth what the market says it is worth, and this could be ten times the underlying cost - or one-tenth of it. As a result, people can make huge profits or go bankrupt, based on supply-and-demand.

Market demand for houses is driven by a number of factors - demographics being one of them. Whenever a new generation of 20-somethings comes of age, demand for "first time" buyer homes will spike. People reach a certain age, usually the late 20's or early 30's and decide they need to nest. It may be a biological urge. Women want a place to settle down and give birth. Men want a fancy cave to show off to their fellow cave-men. It probably goes as far back as that.

Similarly, we are seeing a generation of oldsters die off. When baby boomers drop in droves, the cost of housing in retirement communities may plummet. It remains to be seen. Here on our retirement island, a lot of houses are coming on the market - and being snapped up not by retiring 60-somethings, but vacationing 50-somethings. It is an interesting change in demographics, to say the least.

In addition to demographics, there is also economics. When an area expands economically and jobs are created, the demand for housing booms. When demand slackens, you have a bust. My brother once wrote an article about the oil-shale development in Parachute, Colorado during the Carter years. It was a precursor to the fracking boom we have today, but run by the government. Overnight, houses went up and prices skyrocketed. When Reagan took office, he cancelled the program (and took the solar panels off the roof of the White House) and Parachute became a ghost town in short order.

We see similar things in fracking towns and oil sands towns today. Compounding this problem is overbuilding by developers - each hoping to be the one seated when the music stops. If you don't overbuild, the other fellow will - and reap all the profits. Capitalism is not an exact science.

But regardless of which factor or combination is at work, it boils down to supply and demand and even small changes in supply or demand can cause huge swings in prices which is why, in a real estate bubble, prices skyrocket so quickly and then plummet just as fast. These prices may reflect market value, but the value is transitory - while the 30-year mortgages are not.

To begin with, understanding how prices are affected by demand is important. Even a small drop in demand or a small increase can cause prices to fluctuate wildly.

For example, suppose in a small town there are 100 homes for sale and 99 buyers. Well, clearly, someone's home is not going to sell. So that homeowner will drop his price. As a result, perhaps one of the buyers will buy his house instead. This in turn will cause another homeowner to drop his price. Perhaps if prices drop enough, another buyer will appear to snatch up a bargain.

Conversely, if there are 99 homes for sale and 100 buyers, one buyer is not going to get a house. He might bid up the prices in an attempt to buy a home, which in turn can cause a bidding war.

If the median home price in our mythical town is $100,000, it is not hard to see how a small bidding war, between even a few buyers, can increase home prices by as much as 5-10%, as the incremental monthly cost of ownership is not that great. Similarly, it is not hard to see how even a small discrepancy between the number of sellers and buyers can drop prices dramatically - again by as much as 5-10% without effort. And all this because of a ONE PERCENT difference between buyers and sellers!

So you see, our "housing bubble" was not due to huge demand and the collapse was not due to a huge drop in demand. People still want houses, just not as much as before. If demand drops 5-10%, housing prices can drop 20-30% easily.

Small changes in supply and demand result in huge swings in prices. Most people, including myself, didn't "get" this - until they experience a few bubbles of their own. When prices go up 30% in a year, it doesn't mean demand has gone up 30%, but rather only a few percentage points. Conversely, when demand goes up 1%, it can mean a 10% increase in prices, when supply is limited. And in housing, usually supply is limited, as it takes months if not years to build more houses. There is a lag between demand and supply, which in turn causes problems as builders end up chasing phantom demand, years after the fact.

But what sets the actual price of a house? And this is where it gets tricky. For most working class people, their only option in buying a home is to pay what you can afford to pay on a monthly basis. We are not like the folks buying $30 million apartments in New York - they don't do the math on the monthly overhead cost and whether it would be cheaper to rent. They want a penthouse with a view of Central Park and pay what it costs - and probably pay cash.

The rest of us have to get a mortgage. And how much we pay for a house is based on how much we can afford. And for most people, particularly first-time home buyers, the question is, can I afford this, or would it be better to rent?

And it isn't hard to figure out the answer, with a pencil and piece of paper. Add up the cost of your rent, utilities (if any) and other rental expenses, and you have the monthly cost of renting. And hopefully, this is a smaller number than your monthly paycheck (but in many cases, 1/3 to 1/2 of it - sometimes more!).

Then add up the costs of home ownership - the mortgage, the utilities, taxes, insurance, condo fees or HOA fees, repairs costs, etc. and then subtract any tax benefit (home mortgage interest deduction) and possible appreciation over time. My calculations show that a home doesn't "make money" for you over time in a normal market, but rather the expenses of living there mean that every dollar you spend on your house you might get back when selling it, if you stay there for at least 5-10 years.

This is, of course, better than renting, in the long-term, as when renting, you get nothing back.

But if you stay in a house for less than five years, you may not make back your closing costs - and actually lose money on the deal. If you buy at the height of a bubble and sell when it bursts, you may lose your life's savings. It is a serious thing to consider, and yet so many people buy houses for emotional reasons and based on the most superficial criteria.

In a normal market, the monthly cost of owning a home (for middle-class and starter homes) often tracks rental costs. Usually home ownership costs may be slightly higher, as people "buy ahead" of the market, realizing that rents do indeed go up over time, but a 30-year fixed mortgage may stay the same. But for the most part, in a normal market, the monthly cost of owning a home (with a typical down payment) is not 2-4 times or more the cost of renting.

Markets where it is cheaper to buy than to rent rarely exist, as such houses are snapped up fairly quickly and prices stabilize. Renters are not fools, and would prefer to pay less to live. But bubble markets can expand rapidly in pricing, and this is often due to the use of "funny money" mortgages as well as people signing papers ("liar's loans") and not realizing the consequences, which can take months or years to materialize.

Even if the monthly cost is "affordable" the resale price of the house can vary considerably, leaving the home owner "upside down" on his house.

Florida was a classic example, where all of these factors came into play - at once - and caused prices to drop dramatically. A big part of the Florida debacle in 2008 was over-supply. In Ft. Lauderdale, a number of condo projects "topped out" at the same time, dumping hundreds, if not thousands, of unfinished condos on the market at the same time. There was far more supply than demand, and the market tanked.

Compounding this was the "perfect storm" of higher property taxes, insurance rates, condo fees, and interest rates. If you bought a condo for $500,000 back then (which was not an unusual price!) it may have been "affordable" based on the "promotional" interest rate on an payment-optional loan. The condo fee was low (set artificially low by the developer to encourage sales) and the property taxes seemed reasonable. Insurance in Florida was never cheap, but at $2000 a year, not a deal breaker.

Four hurricanes later and insurance is now $4000 a year. And when you bought the condo, you failed to realize that Broward County would re-assess the unit based on the sales price YOU paid, and your taxes are now a sticky $8000 a year. The Condo fee jacks up as the Board realizes there are no reserves (in violation of State law - whatya gonna do, sue the developer?) and major repairs are due. Oh, and that "funny money mortgage" which had low, low monthly payments, has "reset" and now you actually have to pay the bill - at a much higher interest rate.

Suddenly, your monthly payments have doubled and you can't afford to live there.

Well, no problem, you think. You paid $500,000 for the place, and that was three years ago, so by now, it must be worth $600,000 or more, right?

No. You see, the problem is, the next buyer can't afford much more in monthly payments than you can. And since taxes, condo fees, and insurance are taking a bigger bite out of the monthly pie, that leaves less to service a mortgage.

And how much you can get in a mortgage for $X a month is going to depend on available interest rates. When rates go down, people can borrow more. When rates go up, people can only afford to borrow less. So prices are directly affected by mortgage interest rates and these other ancillary monthly costs.

Cranking the numbers, for the same monthly payment you were making initially, you could service only a mortgage for $250,000, which with a $25,000 down payment, means your $500,000 condo is only worth $275,000.

You're screwed. And there is not much you can do about it. You can try to rent the condo, but since the monthly cost of owning is far higher than the rent, you hemorrhage cash every month. A friend of mine in Atlanta did this - losing $1000 a month to "own" a condo he rented out, for five years, before selling it for what he paid for it.

How to make money in Real Estate! NOT!

So what does this mean about this market? Well interest rates are at an all-time low. What direction do you think they will go? Will we see 2% 30-year fixed-rate mortgages? I doubt it. If interest rates rise - which the Fed has been telegraphing for years now, then mortgage rates will go up. As rates go up, the amount of house a buyer can buy for each $1000 of mortgage payment becomes less.

So, for example, if Cindy Lou Who buys a $100,000 condo in Whoville, and rates rise from 4% to 5%, the cost of paying the P&I on that mortgage goes from $477 to $536. If Cindy has an ARM, she's kind of screwed. But suppose in our mythical town of Whoville, where people can only afford to pay $477 a month for a house, interest rates rise from 4% to 5%? The amount a buyer could borrow would drop accordingly - and using the numbers from that chart, you can calculate the exact amount - $88,992. Cindy Lou Who has lost over $10,000 in the resale price of her Who-Condo, if rates go up one percentage point.

Buying a condo at the Trump Whoville might not be such a good bargain.

And like clockwork, Cindy and all the other Who's of Whoville, stage a protest at the Grinch's bank, because after all, it has to be his fault they signed the loan papers, right?

Now throw in a huge property tax increase, insurance hikes, and a whopping condo fee, and you can see that Cindy might be upside-down on her Who-Condo in short order.

But bear in mind that interest rates alone are not the entire picture. Indeed, today in many parts of the USA, interest rates are at an all-time low and so are housing prices. This is more a factor of lack of demand in areas where there are few jobs and incomes are low. You can buy a nice house in many parts of the country for under $100,000. The same house, near a populated metro area could fetch $500,000.

Interest rates are not the only thing affecting home prices.

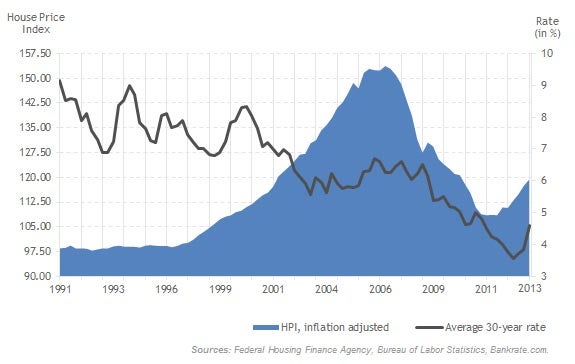

As this article illustrates, during the bubble of 2008, interest rates were higher than they are today, and yet prices skyrocketed. The article does have a few "caveats" and one they didn't address was during that bubble, a lot of people were getting mortgages they weren't entitled to. I myself got a "liar's loan" by merely stating income and assets while the bank officer did an "appraisal" by typing in the zip code into a computer. Today, they want copies of your tax returns, asset statements, and so forth.

In addition, there were the "joke" interest rates that were even lower than today's rates - the catch being that the rates reset after a few years, and the lost interest was folded into the balance of the loan. These were loans designed for the buy-and-flip mentality. Because in addition to interest rates, the easy availability of money as well as tax incentives also affects the home buying decision matrix.

But to look at the chart above and say, "Well, housing prices plummeted in 2009 as interest rates dropped!" is to look at only half the picture. I was buying properties in the 1990's when rates were high. In the early 2000's rates dropped from the 8-9% range (indeed, what I was paying at the time) to the 6-7% range. Again, a small change in interest rates dramatically affects what people can afford. And these lowering rates caused prices to rise.

And rise they did - and then over-shot, as economic conditions (or indeed, any feedback-loop system) tends to do. People lost their shirts, and like with the bubble of 1989 (conveniently missing from this graph!) in the ensuing years (1990-1996) people became very risk-averse about investing in Real Estate. Hmmmm..... maybe I should buy that duplex I saw for sale the other day. With the low interest rates we have today, I could rent that out and..... nah! Too risky!

A Canadian reader writes that in order to "solve" the housing inflation in Toronto, the government is talking about giving first-time home buyers tax credits to help pay closing costs - as well as other incentives to buy. Not only will this not solve the problem of runaway home prices, it will be like throwing gasoline on the fire and the first-time buyers will be the ones burned by the blow-back.

When the government offers monetary incentives to do things, people do them, whether it is buying homes or keeping jobs at a Carrier factory in Indiana. Whether the things you are incentivizing people to do are worthwhile - or even cost-effective - is another story. And whether the incentive just alters prices is another.

For example, if you offer a 10% home buyer credit for first-time buyers, guess what happens to home prices? Yup, they go up 10%. Incentives tend to increase demand (as indeed they are designed to do) and thus drive up prices. And since prices are based on monthly costs, you can raise prices accordingly - almost tracking the incentive exactly. The home mortgage interest deduction didn't "make it easier" to buy a home, some argue, but instead just raised prices of homes by the deduction amount. People pay what they can afford, and when you subsidize an activity, often this just means prices go up.

A lot of folks think the government should just step out of the way and stop meddling in the housing business. This isn't likely to happen anytime soon. During these peaks and valleys, real people get hurt. Voters petition the government for relief. Home builders petition the government for relief. So we end up with rent control, home mortgage interest deductions, tax incentives for first-time home buyers (which we had during the dark days of 2009-2010) and so forth.

What would really stabilize the housing market, though, is stable conditions. If interest rates were predictable, people would be able to lock in low rates and predict housing costs. If property taxes were rational (and not distorted by homestead exemptions and whatnot) people could budget accordingly. If insurance rates were stable, the same is true.

Unfortunately, none of these things is likely to happen anytime soon. And that makes buying a house a little more risky.

UPDATE: A Canadian reader sends these interesting links:

http://www.greaterfool.ca/2016/12/01/the-sucker/

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-12-01/why-2016-may-be-the-year-of-peak-housing-for-canada

http://www.greaterfool.ca/2016/11/29/why-i-rent/

This sounds all so familiar to me. The only difference, the weather was nicer in Ft. Lauderdale!

UPDATE: A Canadian reader sends these interesting links:

http://www.greaterfool.ca/2016/12/01/the-sucker/

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-12-01/why-2016-may-be-the-year-of-peak-housing-for-canada

http://www.greaterfool.ca/2016/11/29/why-i-rent/

This sounds all so familiar to me. The only difference, the weather was nicer in Ft. Lauderdale!