Both Henry Ford and the Wright Brothers started out as bicycle mechanics. And the coincidence is not coincidental!

Most folks don't have a clue about how technology works, and by that, I don't mean how the chips in their smart phones make all those apps run. What I mean is, they have no idea how technology develops and evolves over time.

The narrative we are sold in grade school is that "the great inventors" like Edison, Bell, Marconi, Fulton, and Eli Whitney, tinkered in their backrooms and laboratories and came up with great inventions that changed the world - all by themselves. Today, this myth continues with the idea of the "Silicon Valley Startup" where two guys and a great idea set out to change the world. The garage that Hewlett and Packard tinkered in, is now a shrine. Early Apple computers are cherished as relics of two lone men - Wozniak and Jobs, "inventing" the personal computer.

And the myth lives on. Zit-faced Zuckerberg invented Facebook all by his lonesome, staying up late nights in his dorm room, coding. The truth is a little more nuanced, of course, but we all like to hear the other story. It is like winning the lottery, I guess - we all want to think that the individual can "strike it rich" without the help or aid of anyone else.

And even our Patent system reflects this - awarding exclusive rights to inventions to a single inventor or groups of inventors for inventions that often are created independently and nearly simultaneously by different groups of people in different geographical locations.

The truth is more complex. When you scratch the surface of these stories, you come away with two interesting common denominators - materials science and long felt need.

The first is something most people are not even aware of. "Mat Sci" we used to say in Engineering school, drives all other technologies. When a new material or a new means of making a material become available, new technologies are created with derive from that material.

The low-cost production of aluminum, for example, is what drove the development of the airplane more than anything else. Even in the era of rag-and-stick airplanes, aluminum engines were the key to developing lightweight and powerful powerplants. Langley's steam-powered plane never had a chance!

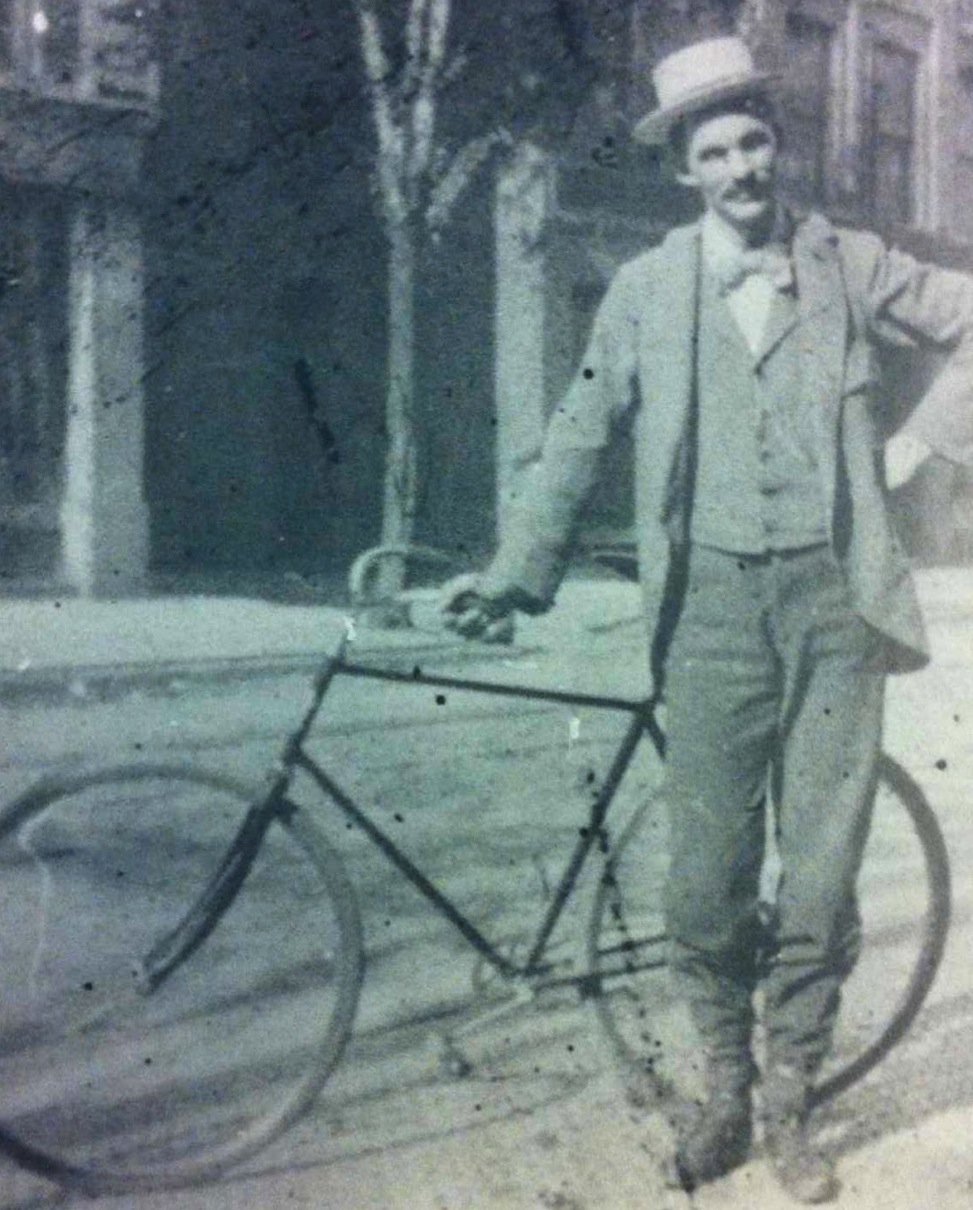

The bicycle, in that regard, was typical of such an evolution, and typical of how one technology leads to another. Bicycles became all the rage in the late 1800's, and once the safety bicycle (today's traditional two-wheeler) became available, the industry really took off. But why did it take so long for bicycles to become popular?

Well, it wasn't until low-cost steel tubing and other components became readily available that bicycles became practical. I saw a bicycle in an antique shop once whose frame was made of bamboo and whose rims were made of wood. It was a primitive thing to be sure, and tellingly, one of the rims was cracked. It did have wire spokes, of course, and a steel chain.

The availability of extrusions to make rims, spokes, and tubing is what drove the business. Once these materials were readily available at a low price, any local monkey-wrench could start a bicycle company by brazing steel tubes together and assembling links of chain. The availability of welding technology certainly accelerated the craze.

It all came together in a perfect storm. And a lot of young men at the time got into the bicycle business as the "next big thing" just as young people today get into computers and software. Older folks might not see where it is going - and many folks don't see it at the time - but it will lead somewhere, that's for sure.

For Henry Ford, it lead to making cars. At that time, cars were more like railroad engines - huge things with massive wooden frames, enormous heavy motors, and gun-carriage-like wheels. These were investment-quality vehicles, sold as bare frames, and then sent to a coachworks to be finished to suit the owner's tastes. Only the very rich could afford them.

Ford had a better idea - that the automobile could be something smaller and lighter. His initial "Quadracycle" was literally a four-wheeled powered bicycle, built in his shop using mostly bicycle components. While this concept would not even carry over to the Model-T, it proved that you could make a lightweight, inexpensive car. In fact, Oldsmobile first picked up this idea with their "curved dash" Olds, which was little more than what we would consider a golf cart, today.

The Wright Brothers followed a similar path, using their bicycle works to support themselves while they tinkered with aeroplanes. They had learned a lot about lightweight manufacturing techniques while building bicycles, and while they started with wood-based designs, eventually small aircraft would center on a brazed or welded tube design which still carries on today with planes like the Piper Cub.

The point is, one technology leads to another. A guy sitting around in a mound of bicycle parts and tubing inevitably thinks, "What else can I build with this?"

The second factor is long felt need which is a term of art in the Patent business often used to negate charges of "obviousness". For almost every great invention ever developed, it turns out that there was a demand for such an invention before it was invented. People opined about flying machines long before they actually existed. The electric light was posited by many as a desirable thing - eliminating house fires from gas or oil-based lighting. It just needed to be invented, of course which was more than a trivial matter.

And so on down the line. Alexander Graham Bell wasn't the only one working on telephones at the time of his invention - he was the first to make one work, though, and the first to get to the Patent Office.

And a lot of people argue, that because of this. maybe we shouldn't be awarding Patents to the first-to-invent or first-to-file. But then again, what drove these inventors into a frenzy of activity was often the incentive of that Patent. So even if it is "unfair" to give one person or group all the glory, it is what motivates people to invent.

For computers, the same is true. The personal computer took off in the 1970's not because of some team of kids working in a garage, but because the microprocessor was developed, initially as a control circuit device. Early Intel 8088, 8086, and 8032 processors were never quite envisioned as the backbone of a computer revolution. At first hobbyists and others assembled primitive machines at home, using the now-ubiquitous cassette tape recorder as a means of storing data (again, a product appears on the market and people say, "what else could I use this for?"). Jobs and Wozniak were just two in a long line of Personal Computer designers, who struck it rich with their first computer, as it was one of the first low-cost PC's (which is what we called all home computers back then!) that was more than a circuit board and a set of assembly instructions.

Again, it was a perfect storm of newly available components (including the DRAM) that drove this revolution, not the machinations of any one person or small group of people.

Today, it is the Internet, and a lot of ideas are being knocked around as being the sole property or invention of one person or group of people, when in fact, the same or similar ideas have sprung up spontaneously all around the world.

In the tech crash of the 1990's, suddenly a lot of server space, spare computers, and office space became available for cheap at bankruptcy auction. Overbuilt fiber-optic networks were available for cheap as well. The idea of e-commerce on the Internet took off, as did a lot of other Internet applications. With all this cheap gear to work with, people could develop ideas that would have been too costly only years before. Sometimes bubbles have dividends!

The idea of "social networking" as we all know, didn't originate in a dorm room at Harvard. There were numerous social networks before Facebook - Friendster, Myspace, Second Life, and so on. What Facebook had going for it was being in the right place and right time when the public was ready for an all-encompassing social network. The best idea, they say, is an idea whose time has come.

And again, we see a pattern - long felt need but also the availability of a new, low-cost resource, in this case, the Internet, which was just starting to become present in nearly every home in America. Prior to that time, Internet penetration wasn't as pervasive as it is today. When the Internet was just a few computer nerds, possibilities were limited. Once everyone was online, well, the possibilities became endless.

So what's the point of all of this? Beats me. I suppose, though, you could look at this phenomenon in a number of ways. For starters, it might help one realize where technology is going next and how to invest accordingly.

As I noted in another posting, the aptly named Motley Fool was hyping the snot out of "3-D Printing" as being "The Next Big Thing!!!" and suggesting you invest in it. And it is a thing, of course, but the companies making these printers are struggling, as they become a commodity item and moreover, not everyone on the planet decided they needed one this year. Some have already gone bankrupt. Early models did little more than 3-D print tiny garden gnomes and most people who bought these early, primitive machines, used them a few times and then shelved them.

But down the road, yes, it will change things. And just as no one really got rich selling bicycles, I doubt anyone will get rich selling 3-D printers by themselves. The key will be the guy who figures out how to make these things indispensable for the average user. Technophiles love them today and like to tinker with them. But how do you get the Facebook crowd excited about them? It has to be more than tiny garden gnomes. Figure that out, and you're a Billionaire.

And so on and so forth. New materials, provided they can become cheap and ubiquitous enough, will change entire industries. Carbon fiber, for example, is slowly morphing from exotic to everyday material, finally replacing the aluminum that birthed the aircraft industry. What new material will be next?

It is hard to predict, but it is an interesting thought experiment to play with. When there is enough of some material lying around for cheap, people instinctively think, "what could I build with this?"